First Tracks: Bill Briggs 2 of 2

Written by Robert Z Cocuzzo

“First to ski the Grand” will forever be etched alongside the name Bill Briggs, propelling the mountaineer into ski immortality. Yet the patriarch of North America’s big mountain skiing measures his life not by those turns in 1971, but by the determined steps that delivered him to the summit. “I had an opportunity to live an awfully rich experience,” he says, stirring his coffee. “You have to understand, all this background is leading up to something like skiing the Grand.” Of course the bootpack was not always easy; Briggs overcame more than his fair share of adversity. So while the history books may crystallize his legacy in that first descent, Bill Briggs’s story speaks to so much more; he is a testament to the power of the human spirit.

“I was generally weaker than all the other guides. I did not have the strength,” Briggs says, looking past us as if his younger self is sat in the next booth. “My chief strength was what I learned from Bob Bates all those years before: to not get flustered by the scene and to figure things out.” Returning from Europe with first ascents in his back pocket, Briggs finally considered himself qualified, and applied to be an Exum guide in Jackson Hole.

North America’s preeminent guide service, Exum Mountain Guides was (and still is) a serious operation, enlisting only the most elite mountaineers. With his application in limbo, Briggs took a job on a road crew, building the highway from Moose to Moran. When laying tar in the summer heat became insufferable, he was hired as a dishwasher at Dornans. All the time, the Tetons loomed over him, a constant reminder of his pursuit.

One August afternoon, an Exum guide quit in the midst of the summer rush. “I happened to be there at the time,” Briggs jovially remembers. “And [Exum director] Brett said to me, ‘Do you want to be a guide?’ I said, ‘yes. ’ He said, ‘O.K. here’s your client, take him up the Grand.” Briggs breaks into a screeching laugh. “Whammo! I’m in!” he manages between breaths. Appropriately enough, he worked alongside Willi Unsoeld, the man who first suggested he become a guide all those years before.

When winter rolled around, Briggs returned east to run a ski school in Vermont. Mind you these are the days before Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. With a cadre of Exum guides as his instructors, it was only a matter of time until Briggs schemed up an adventure to test their trade. In the winter of 1959, he and four fellow Exum guides embarked on an unprecedented traverse in British Colombia, 100 miles from the Bugaboos to Roger’s Pass. “There was no hesitation from those guys!” Briggs says emphatically. “We know skiing, and we know climbing, and we get a chance to use them both to complete a traverse like Fidtjof Nansen did in Greenland? Yeah!”

Without a map (as the traverse was unchartered), and sustaining on minimal rations, Briggs deftly navigated his four-man team through the inhospitable terrain, passing over crevasse–ridden ice fields and down avalanche prone pitches. “It had never been done. And it was a piece of cake,” Briggs says matter-of-factly. “It was a piece of cake for us because all four of us were trained for the job. We were just doing what we do.”

Briggs excuses himself from the table to fetch some photographs from his car. Watching him leave, we notice the old man’s irregular gate; he shifts his weight from one foot to the other as if walking only on his frame. But this is no old football injury; Briggs’s hip is fused. Never mentioned throughout all these tales, he was born without a hip joint. At the age of two, surgeons fashioned one out of his pelvis, setting in motion a slow disintegration of the makeshift joint. By the time he completed the Bugaboo traverse, his hip was nearing its end.

Aware that he would inevitably need to have the hip fused, Briggs set his sights on one final peak: Mount Rainier. After the Bugaboo traverse, it was not enough to just climb Washington’s highest mountain; he had to ski it too. “My hip was finished. I was taking Dexamyl to essentially overcome the pain. But with the help of my team and a French guide, I climbed and skied Rainier,” he remembers. “That was the last thing I was going to do. I go get my hip fused, and that would finish up my career. It’s all over after Rainier.”

Or so he thought.

Restricted to a cast, Briggs was fired from the Exum Mountain Guides as well as from a ski instructor job in California. Like a lonely heart moves away from a lost love, Briggs relocated to New York City to pursue music. Yet no matter how loud he played, no matter how much he yodeled, he could not drone out the call of the mountains. Before long, he cut off the cast, and was back climbing and skiing, well. So well that he was hired back at both positions. “Didn’t change a thing,” Briggs says of his fused hip. “I’m so lucky. You can’t believe how lucky I feel to have a hip like this. Now that’s not just thinking positively. That is the way it is. It’s hard for people to get the concept that I really feel good about having this hip.”

Back in the saddle as an Exum guide, albeit a “junior guide”, Briggs proved just how good this new hip was. During a tour of Teewinot, a client slipped and broke his ankle. Briggs threw the man on his back, and carried him down the mountain. Relishing in the story’s punch line, Briggs exclaims, “When I got to the bottom, Glen says, ‘You’re a senior guide again!’”

Bill Briggs Interview Supplement from The Mountain Pulse on Vimeo.

Briggs’s decent of The Grand Teton came at the sunset of his career. 40 years old, and with several first ascents, descents, and traverses under his belt, he was distinguished in the mountains and most definitely qualified. Yet skiing the 13,775 foot peak represented more than just another first. In The Grand he saw the future of skiing and the authority to herald it in. “I’ve been bugged all the way along by these racers who said ‘the ultimate in skiing is to be a racer.’ Well not necessarily. There is the other end of skiing: ski mountaineering. And that is a perfectly good goal outside of racing.”

Briggs not only progressed the sport, but shattered the cobwebbed European techniques that were still in practice. “You’ve got this screwed up ski teaching, impractical form perpetrated on the public. And this bugged the living daylights out of me,” he says, perking up in his chair. “If I am going to change any of that, I have to establish myself as a skier that no one can question.” The Grand endowed him that authority, and he introduced a new teaching style as the director of The Great American Ski School at Snow King, forever altering the form of Jackson Hole skiers.

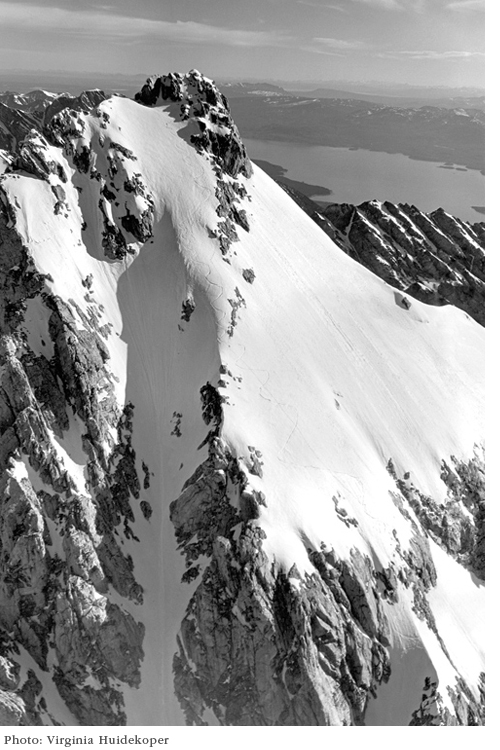

Briggs was also heralding in a new realm of mountaineering. In the lead up to The Grand, during exploratory ski descents of Buck Mountain and Mount Moran, a new element of risk was introduced to the long storied pastime. Briggs and these early ski mountaineers were going off belay to accomplish these descents, entering into a no man’s land of little protection. This came to distinguish American mountaineers between those with the fortitude to do it and the many others without. “We’re talking about a realm of mountaineering where you don’t have an anchor. All of a sudden that’s too far out for an awfully lot of people. What seems okay to me is not okay to so many others that I always considered to be mountaineers,” Briggs says. “This is what’s possible. This is all in the realm of possibility. This is not far out.”

While requiring sheer confidence, Briggs did not consider ski mountaineering as death defying. Every move was calculated, every possible obstacle prepared for. It was a practice he’d been honing his whole life, from Bob Bates to Bugaboos. Ski mountaineering was a natural progression.

And in this sport, Briggs foresaw The Grand as the ultimate qualifier: “This was going to be a big sport. Skiing the Grand was not going to be an unusual thing, this is going to become a usual thing. Anyone who wanted to be a real skier had to do it.”

Yet even with innovations in equipment and the relative luxury of a chartered route, skiing The Grand remains a revered feat to this day, only further illustrating the gravity of Briggs’s accomplishment.

Briggs finishes his coffee and relinquishes a napkin on to the table. The conversation has reached a natural conclusion. Still clinging to the edge of our seats, we slide back and try to let the story settle. Before long, Briggs is up. He extends a crooked hand, and thanks us for breakfast. We shake it, unable to sufficiently express our gratitude. Then he’s off, back to his booth where he sits under that historic picture shot in 1971.

For years to come, the history of big mountain skiing shall be discussed in terms of B.B. and A.B.: Before Briggs and After Briggs. Every turn we make, every bootpack we mount connects to that man in some way. In a sport so exciting for innovation and progression, it is absolutely necessary to remember those who broke the trail. So if you’re grabbing a bite at the Virg some day, look to the far right. Most likely you’ll find an old man huddled over a newspaper, sipping coffee. Shoot him a wave, because the reasons you love this place—the freedom, the adventure— are gifts of a tradition he helped build.

Thank you so much for this! I’ve had the pleasure of talking to Bill at the Stagecoach, while his band takes a break, but there’s never enough time for me to learn all I want. Continue what you’re Doug because it’s awesome!

Great article and w the video technology.. wow taking things to the next level. great writing and great services = a website with a real benificial and profitable future. Dont break the team guys, the machine is starting to run smoothly. long live the Pulse of the Mountains, Thanks you guys. dont let Z drown out their in the Atlantic! the voice is true!